Monthly Archives: January 2020

Kane County considers contract with highly scrutinized video production company

8/12/2019

Kane County officials are poised to embark on a new advertising campaign produced by a company that follows a business model criticized for making overly ambitious promises.

But they may not have to worry about taking a financial risk.

In July, county officials began considering a proposal to pay Florida-based Information Matrix $27,000 to produce three video segments promoting the county. One would be for public television. Another video would be for commercial networks. And a third version would be sent to companies that might like to do business in Kane County.

But after the Daily Herald asked company officials if Information Matrix would refund some or all of the $27,000 if it didn’t fulfill promises to produce millions of viewers in every state in the country, the company informed Kane County that “funding had been secured” to do the project at no cost.

“We do many pro-bono projects every year, and we are excited about working with you and your team!” Anthony Davis, executive producer for Information Matrix, wrote in a letter to county board Chairman Chris Lauzen.

When Lauzen pushed the county board to approve the plan during a public meeting in July, it was the public television video that caught most of the attention of board members. Such videos are typically produced to fill gaps between longer programs in a station’s schedule.

Board member Deb Allan said she is a big fan of PBS and sees short segments promoting other states all the time.

“It makes you want to visit Wisconsin, visit Maine,” she said.

Video production companies contact organizations with offers to create content they promise to be aired on public television stations so frequently that PBS has a warning page about such pitches on its website. It provides links to various news reports dating back to 2008 detailing the various claims made by such production companies.

“While these producers and companies may have content broadcast on public TV or PBS member stations, they do not have a direct relationship with PBS,” reads the statement on the website. “An organization should carefully consider working with any producer requiring fees or costs of production and report them to PBS.”

PBS produces content for public television stations. It is not a television network. Its governing rules prohibit content paid for by the subjects of the programs. And every local public television station has full control over what it decides to air.

Davis told the Daily Herald that past criticism has unfairly focused on confusion about the company’s business relationships and the gripes of a few while ignoring the happy outcomes for hundreds of its other clients.

In email correspondence with the Daily Herald, Information Matrix officials acknowledged there is confusion over how public television and PBS work and what a production company like theirs offers. Such confusion, they said, is the source of any negative attention their business model has received.

Officials said the company has no direct relationship with PBS or any public television station that would give them control over what gets on the air.

The $27,000 in charges in Information Matrix’s original pitch to Kane County were labeled as being independent of the video produced for distribution on public television. The material could not otherwise have a chance of being broadcast on PBS, but the issue became entirely moot when Information Matrix decided to offer its services to the county for free.

The company’s marketing materials also promise the public television segment “will air in all 50 states” and reach “roughly 60 million households.” They pledge the commercial segment will “air 400 times in many of the top 100 direct marketing areas during peak and prime time” on networks like CNN, Fox Business and the Discovery Channel.

Davis and a defamation attorney representing the company acknowledged in a series of email interviews with the Daily Herald that the company can’t guarantee the video will air on any public television stations. For the commercial segment, the company buys airtime at bulk rates and uses “long-term relationships” with networks to secure airings.

If Kane County proceeds with the project, Davis said he will make public the airing affidavits from the networks to verify when and where its videos aired on public and commercial television. Those affidavits will support the company’s marketing promises, he said.

“We literally have hundreds of satisfied clients,” Davis wrote.

Lauzen said he’s not concerned with how often, when or where the videos air, especially the video targeting public television audiences.

“Our audience ain’t PBS,” Lauzen said. “Our audience, my whole career, has been the grass-roots constituents we serve. If (the PBS) part of it was absent, it wouldn’t matter. It’s very secondary in terms of priorities.”

His goal, he said, is to have high-quality videos the county can use to market Kane County as a great place to live, work and raise a family.

“This is not a scam,” Lauzen said. “We wouldn’t spend (constituents’) money unless we’d spend our own money that way.”

The full county board will vote on whether to proceed on Tuesday.

Kane County chairman, state’s attorney renew fight with finger-pointing memos

4/3/2019

Kane County Board Chairman Chris Lauzen called for hiring an independent attorney Wednesday in his ongoing clash with state’s attorney Joe McMahon over union contracts.

Lauzen and McMahon sent dueling memos pointing fingers at each other for lingering confusion over the terms of the contracts.

Lauzen’s memo blames McMahon’s office for “ambiguous” wording in contracts approved in December that Lauzen and as many as 11 board members have since tried, unsuccessfully, to rescind. Rulings by McMahon’s office on the effectiveness of a rescind motion in late December and the votes needed for a second attempt at rescinding the contracts last month stymied the efforts. Lauzen’s memo includes opinions he sought from three outside parliamentarian experts that indicate McMahon’s office erred in rulings about advance notices and voting majority requirements that killed the rescind votes. Lauzen said he paid for those opinions out of his own pocket.

Outside of the memo, Lauzen cited those “errors” as reasons for the county board to hire an attorney independent of McMahon’s office to get second opinions, if so desired.

“We have to stop this civil division from running amok,” Lauzen said in an interview. He said the civil division of McMahon’s office has not been properly supervised since McMahon took on the case of the shooting of Laquan McDonald by Chicago Police Officer Jason Van Dyke. McMahon objected to the hiring of an independent attorney.

“Unlike private attorneys who advocate for individuals, the state’s attorney’s office’s obligation is to the people,” McMahon said.”

McMahon issued his own memo to the board. A copy obtained by the Daily Herald shows it lays out a timeline of emails that suggests his office, the outside counsel negotiating with the unions and county finance director Joe Onzick confirmed with each other, and then with Lauzen, the exact terms of the union contracts before the board approved them in December.

The contracts cover employees in the county clerk, health department and workforce development offices.

The deals were to call for four-year terms, no retroactive pay and 2 percent annual raises. McMahon’s memo says that’s what the contracts include. The problem, McMahon wrote, is Lauzen, at least initially, misunderstood that there would be a 4.04 percent increase in wage expenses in the 2019 fiscal year. Under the new deal, the first raises were to come at the end of the 2018 fiscal year.

The memo includes an email on Dec. 8 from Onzick expressing concern that Lauzen misunderstood the raise dates. That triggered an email from McMahon’s office to the outside labor attorneys requesting a direct contact between them and Lauzen to clear up the misunderstanding. An email on Dec. 10 says the attorneys contacted Lauzen.

However, in a subsequent closed-door meeting about the union contracts, McMahon’s memo indicates county board member Doug Scheflow asked if the first wage check after signing the union contracts would reflect a 4 percent increase. But Lauzen responded by saying it would better to explain it to the public as four years at 2 percent with no payment the first year than as 4 percent, 2 percent, 2 percent.

“These emails reveal who knew what and when about the financial terms of the (union contracts) and the true cost to the county of two raises close in time,” McMahon wrote. “For the chairman to suggest a narrative that he was neither informed of, nor understood the terms of, the (agreements) is inconsistent with the email correspondence between the lawyers and Mr. Onzick and the direct communication between (the labor attorneys) and Mr. Lauzen.”

As far as the parliamentary procedure disagreements, McMahon’s memo says Lauzen’s outside opinions are incorrect.

“They either cited an old version of Robert’s Rules or the attorneys do not appear to have been provided with all the facts,” McMahon wrote.

For instance, one of the opinions suggests the resolution to rescind in March was attached to a published agenda. The resolution was actually distributed for the first time at the meeting, causing the board to take a recess to review the wording.

The full board will meet again next Tuesday.

People living outside in the suburbs: Homeless census ensures they count

1/30/2019

A barrage of fluffy flakes coated a team of Elgin police officers as they parked their squad cars behind a downtown tire shop. It would be the staging area for a once-a-year patrol into the land of the often forgotten.

Exploratory steps took the officers down a slick embankment. Then up onto level ground for a walk along frosted railroad tracks. No one was sure what they’d find with the temperature hitting a low of 13 degrees one night last week.

In past years, on frigid and snowy nights, similar patrols seeking the living instead found some who’d succumbed. Last year’s count included three dead.

The patrol headed down another embankment and into the woods. Despite the snow, the path into Elgin’s poorest neighborhood was visible. The residents are the people you might see sitting on a bench or warming their bones in a parking garage elevator. And most nights, most people would pass while trying not to see them. But tonight, the residents of Elgin’s “Tent City” would be sought out and counted.

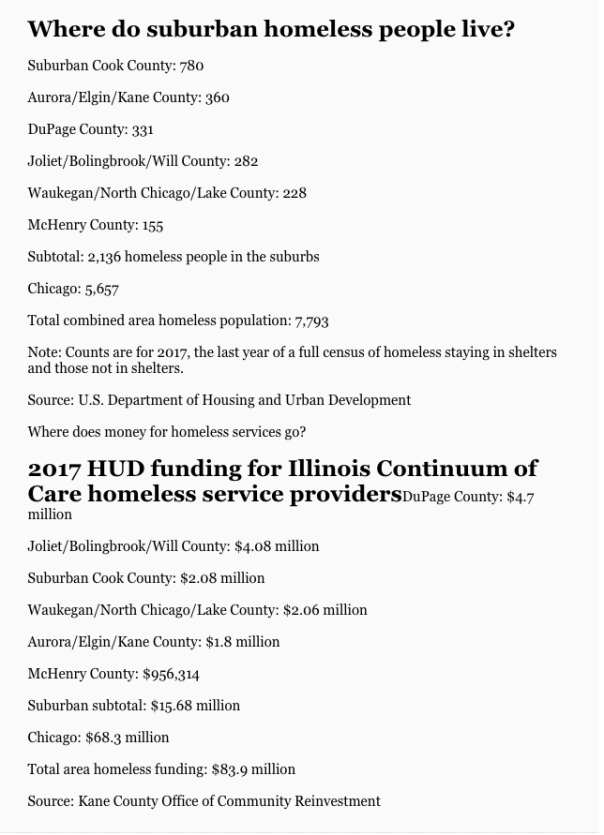

Agencies throughout the country will, or already have, duplicated the effort as part of an annual national census of homeless people. The count helps the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development determine funding to agencies that provide services like emergency housing and job training.

Agencies like Northwest Compass Inc. in Mount Prospect and Lake County will conduct their counts Wednesday night, when temperatures could drop to minus 26.

HUD disbursed $2.1 billion to homeless service agencies in the last funding cycle. About $109 million of that came to Illinois through the 20 umbrella organizations, known as continuums of care, in charge of advising HUD about how to spend the money.

The Aurora/Elgin/Kane County Continuum of Care received $1.77 million. That was an 8.8 percent increase over the preceding year, the largest funding increase in the state.

Heading into Elgin’s count, agencies had no idea when funding information would come through. The reopening of the federal government after a monthlong shutdown allowed HUD officials to make a partial funding announcement over the weekend for agencies awaiting word on renewal grants. The Aurora/Elgin/Kane County continuum will receive its full expected funding. Dollars for new projects are unknown. HUD released no timetable for that announcement as another federal shutdown looms in a few weeks.

“A lot of the funding we receive is to sustain ongoing projects that we renew annually,” said Scott Berger, who oversees Kane County’s homeless management information system. “For those of us at the end of the pipeline, we’re still conducting the work of what is an extension of the federal government at the local level.”

James Harvey knows that work well. He represents the formerly homeless on the Aurora/Elgin/Kane County Continuum of Care Board. During the annual homeless count, he’s shoulder to shoulder with the Elgin police patrolling through Tent City.

Harvey knows the people he will encounter are residents of Tent City by choice.

“In Los Angeles, you see homeless people in the streets,” Harvey said. “But here, people are proactive with the homeless. You can see that here tonight. If someone needs food, if someone needs shelter, it’s out here.

“There’s work. You can get it. So if someone isn’t taking advantage of that, maybe that tells you they don’t want the help. Some people like to drink and just sit. Some have issues with alcohol or drugs or mental health. There is plenty of help here to get a hand up, not a handout. But you can’t make people accept that help.”

As Harvey and the police enter Tent City, the first living quarters they see, a mishmash of tarps and rope, is augmented by a side-view truck mirror tied to a tree for grooming. A sign tacked up at the entrance reads: “Hot Beer. Lousy Food. Bad Service. Welcome. Have A Nice Day.”

As the police shout their presence, a voice comes back from inside the structure letting them know there are two occupants to add to the census — a husband and wife. The questions are the same for each person the police encounter: Are you OK? Do you need anything? Are you aware the shelters are open? How long have you been homeless? Do you have problems with drugs, alcohol or mental health?

The answers are echoed throughout Tent City.

“I’ve got my bases covered,” the voice tells police. “I always plan. We’re fine.”

All the residents police encounter are between their late 30s and early 50s. They’ve all been homeless for more than a year, many of them off and on for more than three years. None admit to problems with drugs or alcohol, though several indicate they believe their neighbors have addictions. A few admit to other problems.

“Do I have mental illness?” chuckles a man who identifies himself as Christopher. “Come on, Lieutenant. You know I do. You know I do!”

Christopher tells police he’s the father of two: a boy and a girl who are 3 and 4 years old. Police confirm no children are present.

The numbers for this year’s homeless census will take several weeks to compile from the various agencies involved. Recent numbers show the local homeless population remains steady regardless of the services provided or what’s happening with the economy.

In even years, the census counts homeless people only in agency shelters. Last year, the Aurora/Elgin/Kane County census counted 430 people. In odd-numbered years, the census includes non-sheltered homeless people, such as the residents of Tent City. In 2017, the local census counted 360 homeless people.

Berger said part of the reason for the steady count is the ease of traveling in and out of the Fox Valley.

“We are part of a dynamic metropolitan area,” Berger said. “Our area is on two interstate tollways that feed into and out of the metro area. There’s an element of what we are dealing with that is very migratory.”

Leanne Deister-Goodwin’s business is meeting that homeless need regardless of where the people come from. She is the executive director of the St. Charles-based Lazarus House. Last year, it provided more than 50,000 meals while housing about 46 people every night in emergency shelters and transitional living programs.

Aside from Kane County’s homeless management information system, which tracks homeless people as they receive local services, Lazarus’ programs are the No. 1 priority for funding in the continuum of care’s annual application for HUD financing.

Deister-Goodwin said Lazarus House always plans for contingencies, including government shutdowns.

Grants or no grants, there will be homeless people throughout the suburbs, Deister-Goodwin said.

“People are usually surprised to learn the majority of our guests are employed,” she said. “Yes, losing a job might be what gets you here, but it’s not always. Lots and lots of things happen to folks in their background before they ring our doorbell.

“Mental illness is prevalent. That could mean depression or anxiety, but that can be serious. And then there’s people who just want the autonomy and choose not to seek help through a shelter like ours. There’s pride and the need for independence.”

Several of the elaborate living structures in Elgin’s Tent City demonstrate that pride. There are patio-style sitting areas. Some have shelving units holding cans, bottles and tools. Bikes are the preferred form of transportation. One living area even has an outhouse of sorts complete with a hole covered by a toilet seat.

While exploring these areas, Elgin police encounter a woman who says her name is Ruby. She’s traveling with an older man named Bryan.

“Hey, they want to know if we’re a couple,” Bryan asks Ruby after a question from one of the officers.

“No!” Ruby replies.

Ruby is on her way to her living area to see her dogs. Two of them were recently stolen by someone Ruby says she tried to sell them to.

“They didn’t want to give me money for them, and they knew they could just come here and take them when I wasn’t around,” she says with a shrug. “I hope they are taking good care of them, and it’s for the best.”

Ruby is known by police for having the “largest piece of riverfront real estate” in Tent City. Ruby smiles in acknowledgment. Her multi-tarp tent structure could house a number of people. Tonight, she’s the only resident who will be counted, though she’s not sure she likes the “homeless” label.

“I’m good,” she tells the officers. “I have everything I need. All of us out here, we’re houseless. We’re not homeless.”

Batavia woman’s outreach to drug addicts is gaining acceptance

4/8/2019

Lyndsay Hartman spends Saturday afternoons sitting in front of death and trying not to think about it.

She loads up her vehicle with needles, Narcan and fentanyl test strips. She drives over to the Kane County Coroner’s office and parks outside the front door with a mission to be a beacon of understanding and opportunity.

Those struggling with addiction can come to her, judgment-free, for supplies she hopes will keep them safe and alive long enough to make another choice to try and get clean. Many who don’t find Hartman at the front door of the coroner’s office increasingly end up coming through the back door in a body bag.

The coroner’s office logged 68 drug overdose deaths in 2018, a record that seems to get broken every year. Hartman already has submitted paperwork to the county health department documenting half a dozen of the overdose saves stemming from the supplies she hands out. Some of those supplies come from the health department.

Getting those supplies from the county and being welcome at the coroner’s office are two of the changes Hartman has seen since she started Point to Point last April that suggest a growing acceptance of the harm-reduction model behind her mission.

Kane County Sheriff Ron Hain said he is both aware and supportive of Hartman’s efforts.

“These are people who are going to be using anyway,” Hain said. “Why not allow them to use safer so that the bigger burden isn’t felt on our health care system? And it begins the conversation of support. That’s the baseline any addict needs. The conversation starts with at least being safe. And, then, if you’re open to it, we have treatment available to you. Lyndsay is becoming an icon for the community to begin helping this population.”

Not everyone sees it that way. Though not pointing to any particular agency, Hain said several local police chiefs will arrest Hartman if they find her in their communities.

“Some have been very black and white in saying it’s illegal,” Hain said. “So there’s that risk (of Hartman being arrested), and she does take on that risk. I don’t know if the state’s attorney would prosecute it or a judge would entertain it, but it’s a risk. As sheriff, I don’t have to move in such black-and-white circles. I can do what’s best for the health and safety of our community.”

Hartman said she doesn’t think about the risk of arrest. It’s just an obstacle to her calling.

“I want people to say this is a good thing, but if that never happens, I’m still going to be out here,” Hartman said. “I’m here for the drug user. They (don’t care) if the health department or police department says they back me. My job is to be an ally and meet them with compassion.”

Local law enforcement isn’t Hartman’s only obstacle. She uses community Facebook pages to advertise her free services. And the backlash from people unfamiliar with harm reduction often trends toward anger.

“My son pays over $600 per month on insulin with insurance,” read one recent comment. “I hope this woman is arrested for aiding junkies.”

Another comment captured a frequent sentiment that there are other people more deserving of help.

“They need to offer free EpiPens to people who need them legitimately before offering free stuff to junkies!!” read the post. “Junkies need rehab not more stuff to enable them to continue using!”

Hartman says those comments come from individuals who lack the ability to see someone addicted to drugs as a fellow human. Because drug addiction involves making at least an initial choice to use drugs, there is a general lack of sympathy. But the choice to eat a poor diet can lead to diabetes. The choice to smoke can lead to lung cancer. Hartman notes no one is saying those people shouldn’t have access to help.

“People have told me straight up that the people I help don’t deserve to breathe,” Hartman said. “That disgusts me to my core. No one wants to overdose. No one wants to be brought back with Narcan. People don’t think they can use more drugs because their friend has Narcan. And Narcan is not comparable to chemo for cancer patients. Narcan is not treatment. Narcan just helps make sure you don’t die. If you had a heart attack because you never stopped eating McDonald’s, no one is going to say don’t use an AED on you. CPR is free.”

A growing segment of Kane County supports Hartman on a personal level. They include the parents of children, young and old, who have died from overdoses.

Stuffing hundreds of tiny cotton balls into Ziploc bags that aren’t much bigger is therapeutic for Carrie Wojcik. The cotton balls are part of the kit Hartman hands out to her clients. They will be used to filter heroin prior to injection. Nearby, on a piano, is the urn that holds the ashes of Wojcik’s daughter Stacie. She thinks about printing small labels with Stacie’s name and the date of her death to put on each of the cotton ball bags.

“People think this only happens on the West Side of Chicago or in downtown Aurora,” Wojcik said. “That’s the stigma. But it’s happening in Batavia. It’s happening in Geneva. It’s in Naperville, St. Charles, any affluent place you can name. It’s there.”

It was March 2017 when Wojcik noticed changes in Stacie. The high school student who scored a 30 on her ACT was attending Waubonsee Community College but not completing her English assignments.

Stacie confessed to the drug use but convinced her mother she had it under control. Wojcik wanted to believe the lie. Five weeks later, two Batavia squad cars pulled up to her home at 7 a.m. to tell her Stacie was dead from an overdose. She’d been missing for two weeks by that point. Officials suggested Wojcik should avoid viewing the body.

“I never got to see her again,” Wojcik said. “She was smart, beautiful, snarky. A good sense of humor. Now I have this pain. It’s something you wouldn’t wish on your worst enemy. And I want people to know that it’s not a normal grief process. There are no steps to getting over it. Because there is no getting over it.”

Wojcik spends a lot of time on Facebook groups created by parents like her, thousands of parents, who have lost children to drugs. That’s where she first learned about what Hartman is doing.

“She’s doing a good thing,” Wojcik said. “She’s keeping people safe. I hope a person who gets one of these cotton balls from Lyndsay at least one time asks her about how to get help.”

Those are the moments Hartman hopes for, too. But she has a never-ending sense of not doing enough. She knows there are many more places where she needs to be to reach people struggling, the people she refers to as “my loves.” She knows she needs to become an official not-for-profit. In the moments when she’s feeling a little less protective about her operation, she dreams of having more people to distribute supplies.

For now, she’s on call. Whenever, wherever, whatever people with drug addictions need. And she tries not to think about any of the people she’s helping coming through the rear entrance of the coroner’s building.

“I can’t think about that, I panic when I don’t hear from the people I’m working with,” Hartman said. “I start obsessively texting or calling. ‘Are you sick? Are you safe?’ Sometimes I’ll check in with someone, and they are like ‘I’m not doing that anymore. You don’t need to contact me.’ That’s good.

“On the other hand, maybe someone overdoses several times. Maybe it’s six times in a month. But then maybe they go 30 days clean. Maybe longer the next time. Until they don’t need me, I’m here. I just hope for the best.”

St. Charles man who killed twin daughters, self, sought treatment, guns

5/10/2018

Randy Coffland knew the depths of depression well. He’d tried therapy. He’d taken an increasing amount of antidepressants. But by January 2017, Coffland began shutting out family and making threats no one took seriously until it was too late.

When all the mental health treatments failed, he erased his twin daughters’ names from his life insurance policy. On March 10, he murdered them in his St. Charles apartment, shot his wife and killed himself.

Now his widow, Anjum Coffland, is fighting to undo that change to Randy’s life insurance policy. Litigation filed this week argues Randy was not of sound mind when he made his brother and a friend the beneficiaries of his $500,000 policy.

Burt Brown, the attorney representing Anjum in the case, acknowledged his client has an “uphill battle” to reverse the beneficiary changes in the insurance policy because the holder is presumed to have a right to make changes and Randy is deceased and can’t be called to testify.

“It’s a very sad situation. Whenever kids get killed, it’s extremely sad,” Brown said. “We’re trying to say he didn’t know what he was doing when he did it right on the heels of murdering in his own children.”

Medical information in Kane County coroner’s records indicates Coffland struggled with mental health for years, pursuing firearms at the same time he pursued treatment.

From seeking help to causing harm

Randy Coffland sought treatment for anxiety and depression on June 8, 2015. He told a therapist his mother and grandmother had psychiatric histories. He began taking a prescription antidepressant.

On July 8, 2015, Illinois State Police issued Coffland a Firearm Owners Identification card. The application requires a response from the state within 30 days.

Coffland stopped taking the antidepressants only weeks later.

But for a time, it seemed, Coffland found some peace. His Twitter page at the time is filled with posts about kayaking on the Fox River, enjoying the pet parade in his hometown of LaGrange, and tips on how to stop bad habits.

But on Feb. 8, 2017, St. Charles police responded to a domestic incident between Coffland and his wife. An audio recording indicates Anjum called 911 because she wanted to go to Randy’s residence to get her work computer. But she was afraid. They had just gotten into an argument that resulted in Randy breaking her cellphone and driving off in her car.

It’s not clear what happened once the police responded to the call. St. Charles police refuse to release the report. They’ve characterized the case as involving no physical violence. No arrests were made.

Subsequent to the murders, Anjum told family members Randy had made multiple threats about killing the girls and himself as much as two months before he followed through. It’s unknown whether she told police about those threats as part of the basis of any of her fears.

Even for police, determining if Coffland had a weapon to follow through on his threats is not easy. If a threat is made about the use of a firearm, St. Charles police will check to see whether the person has a Firearm Owners Identification card, a possible indicator of the ability to carry out that threat.

But possession of a FOID card is not a guarantee someone owns a gun. Illinois does not have a gun registry for police to check for actual ownership.

In an actual domestic battery case involving physical violence, Deputy Police Chief David Kintz said, surrender of a FOID card and weapons becomes a condition of bond when an arrest is made. The February emergency call didn’t reach that level.

Whatever happened at Randy’s residence Feb. 8 didn’t end there. A Geneva police report shows Randy and Anjum ended up at Delnor Hospital the next day. That’s the same day Anjum later told police she left Randy and moved into her own apartment nearby.

During the visit to Delnor, Randy told police he didn’t own a gun. For a short time, that was true.

According to the coroner’s records, Randy found an old bottle of his antidepressants and began self-medicating about the time when Anjum left him. On Feb. 21, Coffland went to a doctor to discuss what he described as “increasing anxiety” for the prior three to four months. The doctor diagnosed him with “a major depressive disorder” and prescribed Venlafaxine.

Anjum Coffland’s new lawsuit points to one of the possible side effects of that antidepressant — suicidal thoughts — as a possible factor in the events that followed.

“In the days and weeks prior to the murder-suicide, decedent Randall R. Coffland demonstrated that he could not act in a reasonable manner, nor appreciate the nature and consequences of his actions,” the lawsuit argues.

The day after Randy received his new prescription he bought a 9 mm Smith & Wesson handgun. A week after that, on March 1, he phoned his doctor’s office to complain the new medication had no effect. The doctor increased the dose.

Two days later, Coffland made a change to his life insurance policy. He deleted his daughters as the beneficiaries. In their place, he substituted his brother, Russell, and a friend who lived in Glendale Heights. They would receive a 50-50 split of the money.

On March 5, a Sunday, Randy Coffland purchased a second Smith & Wesson handgun. Illinois has a 72-hour waiting period for handgun purchases. By early Friday evening, his daughters were dead.

He lured Anjum to the apartment by telling her he “had secrets, too.” When she arrived, Coffland immobilized her by shooting her in the legs. Randy then called the police to confess his crimes. On the audio recording of that call, Randy tells Anjum, “I want you to live and suffer like I did.”

He killed himself before police arrived. Officers recovered two handguns from the scene.

The lawsuit is next due in court Nov. 29. Anjum’s attorney says Randy’s life insurance policy pays out, even following a suicide, once the policy is more than two years old. Randy obtained the policy 10 years ago.

There is a separate probate hearing regarding Coffland’s other assets due in court Sept. 20. The records in that case indicate Coffland’s total estate may be worth as much as $1.5 million.

Batavia woman provides clean needles, naloxone to drug addicts

4/23/2018

Lyndsay Hartman’s calling started with a love she couldn’t fix. It was the kind of love that demanded everything. It was broken and frustrating in ways more suburban residents are learning first hand. When Hartman’s relationship failed, it could have extinguished her. Instead, it lit a different fire.

“I loved an addict for a very long time,” Hartman said in an explanatory video on her Facebook page. “It’s hard to love someone who is addicted to drugs. You think that you can fix it, or that you can make it better, or keep them clean. You can’t. I loved my addict. He is now living his life without me. But the lessons he taught me are why I’m doing what I’m doing now.”

What Hartman is doing now is a first for the Western suburbs. She created a one-woman needle exchange program from the trunk of her car called Point to Point Kane County. The program invites people who use needles to inject drugs to call her confidentially at a number in Batavia when they need clean syringes or want free access to naloxone, the opioid overdose reversal drug. In trade, Hartman collects the used needles for proper disposal.

Supplying free needles to people addicted to drugs is a practice ripe for local criticism. Batavia sits in Kane County. The county board rejected zoning for a would-be drug addiction treatment center twice in the past two years. Wheaton, in neighboring DuPage County, rejected a drug-treatment center earlier this year. Mixed into all those decisions was a flood of concerns from local residents about rehab centers bringing drug addicts into their neighborhoods.

Hartman’s ideal vision for her program involves establishing regular hours where people who want needles or naloxone can meet her at an intersection or outside a library to get them. It may start with only a few people. Hartman believes word-of-mouth and a base of trust will bring out more and more people in search of safe injection supplies. When that comes, Hartman said she knows scrutiny will follow.

“The way I see it is I have stuff; they need stuff. And that’s it,” Hartman said. “But I’m not naive. It’s not like I’m opening a lemonade stand.”

There are no laws against the free distribution of syringes or naloxone. Hartman’s model and supplies are drawn from an existing needle exchange success story in Chicago. It dates back to the height of the AIDS epidemic.

The denial persists

John Gutenson was a drug addict long before he joined the staff of the Chicago Recovery Alliance. He’s spent the last 15 years in Stone Park serving as the westernmost distribution point for the alliance’s needle exchange program. That distribution point is the office in Gutenson’s personal home. A large number of the people who get needles from him come from farther west, he said. He knows, on a personal basis, the idea that drug users don’t already exist in large numbers in the Western suburbs is “definitely bologna.” But the denial persists.

“I’ve walked into plenty of police stations out here to talk about what I’m doing, and their reactions are all the same,” Gutenson said. “They don’t feel they have a drug issue. The reality is the opioid epidemic is not a new phenomenon. People have been dying out here for years and years. It’s only now that it’s touching the kids and families of people of some means and who vote that it’s become something that needs to be addressed.”

Treatment is ideal, Gutenson said. But drug users don’t stop using until they are ready. The absence of treatment centers, and the continual fight by suburban residents against them, make it less likely people will seek treatment.

“Naloxone, it keeps people alive, but it keeps them doing the same thing,” Gutenson said. “But if you give them another option, then they may make that move. Death changes people. Even if you only die for a minute, it’s a scary proposition. Treatment has to be available. If not, you may get to the point where you have it in your mind that, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore. I wish I had a way out.’ If treatment isn’t available, there is no way out.”

Building trust

Hartman said she saw firsthand why communities need people like her to make naloxone available to people using drugs. When her ex-boyfriend overdosed, police arrived and administered naloxone, saving his life. But while her boyfriend was at the hospital, police found he had an outstanding warrant for failure to appear in court.

“He just came out of his overdose, and the police handcuffed him, took him out of the hospital, and took him to jail,” Hartman said. “He could have just died, but I didn’t get to take him home. I had to watch him get put in handcuffs. It’s fantastic that police have naloxone now. But if a person dies because they are scared to call the police because of repercussions like that, I have a huge problem with that.”

Building trust without judgment is a key concept in the “harm reduction” philosophy that serves as the basis for the Chicago Recovery Alliance’s approach to needle exchange. Suzanne Carlberg-Racich, director of research for the nonprofit group, said trying to force people into treatment is a tactic that often fails.

“The second you judge someone, you’ve kind of lost them,” Carlberg-Racich said. “Harm reduction recognizes that not everybody has the capacity or the will to change overnight. We don’t have an agenda that somebody ends up as a person who is abstinent from drugs or goes into treatment. But treatment is one of the many options we might offer or someone might choose. Very often people ask us to help connect them to treatment. But, in the meantime, they can’t go into recovery if they die.”

Carlberg-Racich said there is no scientific evidence that shows making clean needles and naloxone widely available increases drug use or pushes existing drug users toward injection methods.

“That’s like saying silverware is what makes you eat,” she said. “The needles are just a vehicle for getting the drug into someone’s body. Without us, people would still find a syringe and get the drug into their bodies. They’d keep using the same needle hundreds of times, share dirty needles with other users or even raid the garbage of diabetics.”

The research may support Hartman’s efforts, but it won’t erase the barriers not having a buy-in from the surrounding powers may create. Hartman has not had any contact with county or municipal officials to discuss her plans.

Batavia police, when contacted for an interview for this story, said they were unaware of Hartman’s operation, but it deserved some investigation.

Barb Jeffers, executive director of the Kane County Health Department, said Hartman should connect with all the community organizations who are also interested in addressing the opioid epidemic. Jeffers said there’s too much potential for something to go wrong when any one person goes it alone.

“What’s her backup if she finds herself in a difficult situation?” Jeffers said. “And what’s the data showing Batavia needs this kind of operation rather than Elgin or Aurora? I get her passion to help others, but keeping yourself safe and others safe is important, too. And you do have lots of people she could connect with out here who are also very interested in solving this problem.”

Hartman said she does intend to contact the police and other community groups about her efforts.

But she will move forward with or without their support.

She already has a Point to Point Kane County Facebook page advertising the availability of clean needles and naloxone by calling (630) 492-1454.

“I’m confident because that’s my personality,” Hartman said. “I have to be confident. I trust that things will work out. I don’t have anything I’m charging money for. I’m not out there to get anyone in trouble. And I’m not scared. For the people who need this service, I’m an ally.”

Former Kane Co. Board member’s new job may pose ethical question

6/9/2017

Former Kane County Board member Brian Pollock spent the past five months saving the county $100,000 per election. But that work, and his $78,000 salary, might violate the same county ethics law Pollock and others describe as weak and unenforceable.

Pollock’s new boss says any questions about the job are petty politics that would not survive a legal inquiry.

A Democrat, Pollock served on the county board from December 2012 until December 2016. He was unseated in November by board member Angie Thomas.

On Jan. 5, Kane County Clerk Jack Cunningham hired Pollock as an alternative language coordinator.

The county’s ethics ordinance bans elected officials from soliciting or seeking employment with the county for one year after leaving office.

The state’s attorney’s office does not comment on the presence of ethics complaints, but the rule itself sits on a precarious foundation. State’s Attorney Joe McMahon, and his predecessor John Barsanti (now a local judge), both deemed the ordinance unenforceable after it came on the books in 2010.

As a candidate, Pollock said he did not support “unenforceable” ordinances on a Daily Herald candidate questionnaire that asked about the law.

“The weak ordinance discussed by the board this year (2012) lacked accountability and enforcement mechanisms,” Pollock wrote. “The county board should focus on passing a strong and enforceable ethics ordinance rather than engaging in political theater.”

Following Cunningham’s 2017 budget proposal last year, Pollock joined his fellow county board members in approving a plan to leave the alternative language coordinator position vacant to start the year. The budget included a line item cost of $42,000 that would enable Cunningham to fill the slot.

The county’s finance department and Pollock himself, describe his position as a 30-hour-per-week, part-time role. But instead of the $42,000 cost of the position, the finance department projects Pollock’s earnings for this year to be $78,000. He also receives health and dental insurance as well as pension benefits.

The net impact of Pollock’s job might still be a financial win for the county. Pollock said he serves a dual role for the clerk’s office. Part of his duties help ensure the county has the proper number of bilingual election judges at polling places.

His other role involves advocating for the clerk’s office on initiatives that could save money. That’s a similar function to what Pollock performed while he was chairman of the county board’s legislative committee. Pollock said he’s not a lobbyist. However, he did push local state lawmakers to craft legislation that would allow for fewer election judges at polling places, particularly when multiple precincts vote at the same location. The legislation awaits the governor’s signature and could save the county $100,000 per election.

Pollock deferred comment about the ethics ordinance to the clerk.

Cunningham, a Republican, said he coveted Pollock’s abilities to work across party lines and find ways to save money back when Pollock was a county board member. Cunningham didn’t hesitate to offer Pollock a job in January.

“I try to cut costs and get more money into the county any way I can,” Cunningham said. “Brian showed a great ability to do that as a county board member. If the rule says I can’t hire him for a year after he leaves office, then I don’t think that’s a good rule. This guy has been a great asset to my office. I’m keeping him on until I’m told not to. If someone has a problem with that, take it through the (complaint) process.”

State law gives elected department heads control over their own offices. The county board only can approve a budget for a department. Once the money is given, it’s up to the elected department heads to spend the money any way they want, including hiring. Ethics complaints flow through McMahon’s office. The existence of such complaints are generally not made public unless they result in legal action.

Employee who accused Kane County chairman of intimidation gets six-figure separation deal

5/25/2017

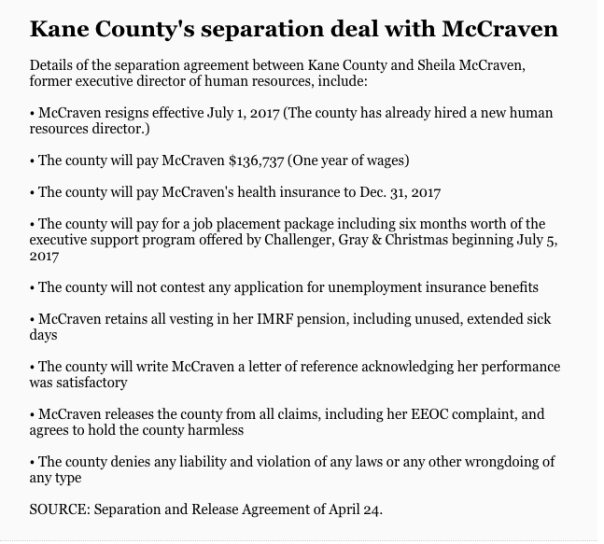

Kane County officials recently closed on a six-figure severance package for an employee who filed a federal complaint claiming Chairman Chris Lauzen engaged in a pattern of “harassment, intimidation and demotion.”

The agreement marks the second documented instance of an employee accusing him of unprofessional behavior.

The situation began to boil in September, according to documents obtained by the Daily Herald.

It was then the county hired an outside attorney to investigate claims of at least three employees alleging inappropriate conduct by Don Biggs, Lauzen’s hand-picked executive director of building management. In a series of letters between Lauzen and Sheila McCraven, the county’s executive director of human resources, Lauzen accuses McCraven of not following his orders and directives from the county board by not appearing at interviews and meetings regarding what Lauzen described as “the so-called investigation” of Biggs.

McCraven did not respond to an interview request and Lauzen directed questions to the state’s attorney’s office.

“This was a personnel interview and not a public meeting; therefore no notice was appropriate,” Lauzen wrote in a Sept. 14 letter. “You refused to attend the scheduled and board-instructed meeting.”

McCraven, in response, indicates she did not participate in the meetings at the advice of the state’s attorney’s office. McCraven said it wasn’t made clear she needed to attend and the state’s attorney’s office had concerns the meetings did not fulfill the obligations of the Illinois Open Meetings Act.

“I perceived your memo to me to be an attempt to intimidate me,” McCraven replied in a letter the same day. “I will not tolerate it. I am an employee of the Kane County Board and have been so for 24 years. In that time and at all times since 1992, I have conducted myself in a respectful and professional manner. I ask that you do the same.”

Five days later, Lauzen responds in a memo accusing McCraven of failing to schedule and post another meeting regarding an “urgent personnel issue.”

“As you recently reminded me, you have worked here for 24 years, so this task was easily within your experience and capabilities,” Lauzen wrote. “Yet you failed to schedule and post this time-sensitive and important meeting. Please tell me why in writing by the end of the day.”

McCraven responded by filing an employment discrimination complaint with the Equal Employment and Opportunity Commission. In the allegations, McCraven notes she filed a complaint of disability discrimination at some point during her employment.

“Subsequently, I have been subjected to intense work scrutiny, intimidation and different terms and conditions of my employment than my fellow co-workers including, but not limited to, working in a hostile environment,” McCraven wrote.

On Oct. 24, McCraven wrote a letter to State’s Attorney Joe McMahon explaining why she filed the EEOC complaint.

“The disclosure of my role in bringing forth the allegations of wrongdoing expressed by three employees in the building management department about Director Biggs has led to a work environment in which Chairman Lauzen is becoming increasingly hostile to me,” McCraven wrote.

She went on to detail a meeting Sept. 19 where Lauzen watched as Biggs “verbally assaulted me for 1½ hours.” She also details Lauzen’s accusations about McCraven inviting the IRS to audit the county, resulting in a $283,000 bill in back taxes and fines. McCraven denied the accusation. The IRS determined the county misclassified some employees as subcontractors, a finding first reached during an audit by the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund.

McCraven also told McMahon that Lauzen disclosed during a staff meeting the confidential EEOC charges to the entire panel of executive directors who report to Lauzen.

“This was totally inappropriate conduct by Chairman Lauzen,” McCraven wrote. “This nonsense must stop now.”

At the same time, Lauzen sent a letter to Pat Kinnally, the attorney assigned to the county board, asking for help dealing with McCraven’s EEOC complaint. In the correspondence, Lauzen said he believes McCraven’s EEOC complaint originated because, “Sheila has misconstrued simple, important questions from me to her.” Then Lauzen includes a plea for help.

“I have asked three times for ‘labor law specialist’ help and been denied three times,” Lauzen wrote. “I will do my best but really should not be on my own. I never imagined that, when I asked attorneys assigned to me for help, that they would deny me assistance and perhaps conclude that I would make better decisions without their help. Are the county and I being intentionally placed in danger?”

Two days later, McMahon sent a letter to county board members informing them he would appoint an outside attorney to represent the county.

EEOC complaints are not public documents unless or until charges result. County officials familiar with what happened next said three things became clear: The investigation into Biggs’ conduct fell apart but was resolved by reassigning some of the employees involved; McCraven’s EEOC complaint probably didn’t have enough support to move forward; and the relationship between McCraven and Lauzen was irreparable. Work began on a separation agreement.

County board officials signed off on the deal earlier this month. Part of the agreement, which includes a year’s salary of $136,737, requires McCraven and the county to not make any statements to the public, media or prospective employers that “may tend to disparage, reflect negatively, or be critical of each other.”

McCraven’s departure marks the second documented incident of an employee leaving their job at the county after a falling out with Lauzen. In February 2014, Cheryl Maraffio resigned as Lauzen’s hand-picked community outreach coordinator, citing “an obvious, significant lack of professional courtesy and respect for me, my work, and my commitment to Kane County” in a letter to the county board.

St. Charles boy’s rare illness underscores need for epilepsy research

2/21/2017

Melissa and Rob Williams’ parenting nightmare began with the sounds of laughter in the kitchen.

Essley, the couple’s 2-year-old daughter, was playing with her 7-month-old brother, Emmett. But when Melissa came in to join the fun, the sight of Emmett’s bobbing head didn’t make her laugh.

“I looked at what he was doing and thought, ‘That’s weird,'” she recalled.

Five days later, the St. Charles family found themselves in a hospital room. Sensors and tubes covered Emmett’s body as Melissa and Rob stared at the display screen of an EEG monitor and sought Google’s counsel on how to interpret what they saw. Doctors would tell them Emmett had a rare form of epilepsy that, in most cases, causes major developmental problems.

The best hope for Emmett, they said, would be to never figure out exactly what was wrong.

About 3 million people nationwide have some form of epilepsy, according to the Epilepsy Foundation of Greater Chicago. In the metropolitan area, about 130,000 people have the condition, and of those, about 20,000 are children.

They have one common goal — stop the seizures. That goal is just as far away as it was 40 years ago when epilepsy research began making progress in treatment, Epilepsy Foundation CEO Kurt Florian said.

“The area we need to be spending more money and time on is research,” he said. “If you go back 40 years, there were two big drugs that people could take and get, more or less, control of their seizures in about 60 percent of cases. Now we have about 20 drugs out there, with way less side effects, but we’re still at a significant level of people who don’t get control over their seizures. We haven’t really gotten any better at getting control over epilepsy.”

Infantile spasms

The key with infantile spasms is identifying the spasms as soon as possible and stopping them.

The spasms are easy to miss. They don’t involve any dramatic thrashing or violent movements. They are as short as a hiccup or the movement a baby makes when startled. At worst, they resemble a baby with the very common problem of reflux.

“They didn’t look like seizures at all,” Melissa Williams said. “But the way his eyes moved up, it just looked odd.”

Melissa had gone through all the hazing about being a paranoid mom with the birth of Essley. She knew the worst part about being paranoid was being told you were paranoid.

She took video of Emmett’s spasms and showed them to other parents. They dismissed them as normal baby movements. But they kept happening. And they didn’t seem normal to Melissa.

She decided her peace of mind was worth the paranoia. A trip to the pediatrician led to a referral to Dr. Steven Coker, a pediatric neurologist with Northwestern Medicine.

Then came the tubes and sensors. An MRI. An EEG. A spinal tap. Genetic testing.

“At that point, I was catching every third word coming from the doctors and nurses,” Rob Williams said. “It was just this sense of, ‘What is happening?’ I felt like I was watching this whole thing unfold in the third person, like a movie, but it was my son, and it was happening to us.”

Dr. Coker’s diagnosis — infantile spasms — devastated Melissa and Rob. They’d read about the condition online. And they knew it meant the window for Emmett having the best outcome closed a little more every time he had a spasm. Melissa went to the hospital cafeteria and “ugly cried.”

“All these statistics hit me about how this could be really, really bad,” she said.

At its heart, “epilepsy” is a term that describes uncontrolled electrical activity in the brain. But that activity can result in a host of physical and neurological problems. In children, it can impede development. With infantile spasms, a baby who had started to crawl, turn over and babble can regress back to a stage similar to the first weeks of life at home.

Melissa and Rob struggled with the question that would be on any parent’s mind — why?

There are hundreds of causes for epilepsy. They range from structural problems in the brain to brain trauma and 87 known genetic causes. With many medical conditions, treatment relies on figuring out the cause of the problem. Dr. Coker told Melissa and Rob to pray for the unknown.

“With infantile spasms, if we find a cause, that may not be good,” Coker said. “Once we know, then the outcome for that patient takes on whatever disease caused the spasm. But if we do all the testing and find nothing, that’s probably the best outcome.”

Stop the spasms

Coker’s strategy was to employ an aggressive regimen of hormones. For nearly nine weeks, Melissa and Rob would inject Emmett in the leg twice a day with a $34,000 gel that would stimulate his adrenal gland to create its own super dose of steroids.

They crossed their fingers. There are no double-blind, controlled studies that formed the playbook to treat infantile spasms. Coker relied on his experience and “just logic” to inform his strategy: Stop the spasms. Do it fast.

The side effects were severe. Emmett had an insatiable hunger that required nursing and jars of baby food day and night. He wanted to be held all the time, resulting in Melissa and Rob sleeping with Emmett in their arms while sitting up every night. He didn’t smile for 10 days.

Melissa recorded her feelings on her blog: “I am terrified,” she wrote. “This is hell. But I believe. Just like I had a strong maternal instinct that told me something was wrong when it looked like absolutely nothing, I have a strong instinct telling me that Emmett is going to pull through this one and be one of the exceptions.”

If infantile spasms are a rare condition, then having the best outcome after its diagnosis is an even bigger outlier. Between 80 percent and 90 percent of children diagnosed with infantile spasms have long-term neurological problems.

Even in situations considered to be the best outcomes, about 70 percent of those children will have problems, such as other forms of epilepsy, down the road. It could happen months later. It could happen years later. Or never at all.

Emmett has not had a seizure for about six months. Melissa and Rob are nervous optimists.

“From here on, it’s the not knowing that’s the hardest,” Rob said. “It could be years before we see a speech delay or some other problem. And you keep waiting for it. The best way for me to handle it is to just feel very lucky and that, deep down, he’s going to be OK regardless of what happens. If there’s any setbacks, delays, I just believe he’s going to be fine, regardless.”

Chicago women’s march draws huge crowd day after inauguration

1/21/2017

On an unusually warm January morning, peaceful protesters of Donald Trump’s presidency decorated major stretches of downtown Chicago with slogans of anger, fear and hope to turn up the heat on an administration just 24 hours old.

The demonstration coincided with similar rallies held across the nation and around the globe. In Chicago, a larger-than-expected crowd that numbered as many 250,000 according to some estimates packed city streets. There were no arrests associated with the gathering, Chicago police said.

A bus stop shelter with “Die Fascist Scum” spray-painted on the side characterized the angry aspect of the spectrum of protesters. Just down Congress Parkway, a picket sign attached to a stroller for two read “Love Not Hate Makes America Great.”

Carolyn Shannon, of St. Charles, dressed in the pink color that characterized the garb of many in a crowd that was mostly female but decidedly representative of many gender identities.

“I feel a responsibility to speak out when I see injustice,” Shannon said. “And right now I see a president who doesn’t seem interested in protecting everyone’s rights. And that’s contrary to what I believe this country stands for.”

In the days leading up the march, organizers anticipated about 50,000 would participate. But thousands more showed up, forcing organizers to cancel the marching portion of The Women’s March on Chicago, but the majority of protesters went along the route anyway.

Police spokesman Anthony Guglielmi said on Twitter at around 11:30 a.m. that the Women’s March on Chicago had transitioned into a support rally at Grant Park. But it was right about that same time that a segment of the attendees broke off and walked the preplanned route.

The segment was large enough to stretch several city blocks as they marched and chanted past the Chicago Board of Trade, federal building and Cook County offices in a loop that concluded back at Grant Park. Volunteer marshals associated with the rally, with the help and cooperation of Chicago police, herded the swarm west down Van Buren and other main streets, blocking traffic but meeting few honks in protest.

Jeannie Cormier Scown, of Geneva, did not partake in the spontaneous march. But she did attend the rally as a show of what progressives can do when properly motivated. Scown said it’s imperative to keep the momentum going into both local and national elections. Electing progressive Democrats to buffer the Trump agenda is the only way to make it through the next four years, she said.

“What this rally is doing is not scaring Trump one bit,” Scown said. “But it is scaring the Republican representatives in our state and in other states. This is a wake-up call to people who are comfortable to start showing up at our county boards and city councils. If those people don’t start turning out, they are going to find no comfort in this next four years.”

In November, it was Trump supporters who turned out. But there were few signs of any counter protests in support of Trump Saturday. At the corner of Dearborn and Washington, a man chanted, “Let’s go, Donald,” as the tip of the largest throng of marchers approached. When the marchers reached his spot, he stopped chanting and walked away, refusing to identify himself.

The event began with a rally at 10 a.m. in and around Grant Park, and the protesters were supposed to start marching at 11:30 a.m.

At the rally, which was hosted along Grant Park at the intersection of Columbus Drive and Jackson Boulevard, thousands listened to speakers including politicians Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan, Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle and several aldermen. Members of the Chicago cast of “Hamilton” spoke and then sang “Let it Be,” according to ABC 7 Chicago.

Diane Kenney Handler, of Elgin, said she could not even bring herself to watch Trump’s inauguration speech because she feared it would be laced with “hateful language.” She said the upbeat vibe of Saturday’s rally helped soothe her lingering frustration about Trump’s victory.

“I’m trying to remain open and hopeful,” she said. “Where we agree, and we can work together with this administration, I hope to do that. But if they keep up the stuff they’ve been saying, they are going to have a fight. I’m here for my daughters. They are young. But I’m older.”

• Daily Herald staff writers Doug T. Graham and Katlyn Smith contributed to this report.